Book V of the Wealth of Nations, ‘Of the Revenue of the Sovereign or Commonwealth’ concludes Smith’s magnum opus. Having criticised the existing state of government involvement in the economy in Book IV, Smith uses Book V to outline his principles regarding when and how governments should intervene in the economy. He sets out the obligation of the state to care for its citizens, proposes theories of taxation, advocating for taxation proportional to income, in addition to land values taxes, and describes a theory of public goods.

“The third and last duty of the sovereign or commonwealth is that of erecting and maintaining those public institutions and those public works, which, though they may be in the highest degree advantageous to a great society, are, however, of such a nature that the profit could never repay the expense to any individual or small number of individuals”

Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations: Book V

“How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it.”

Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments

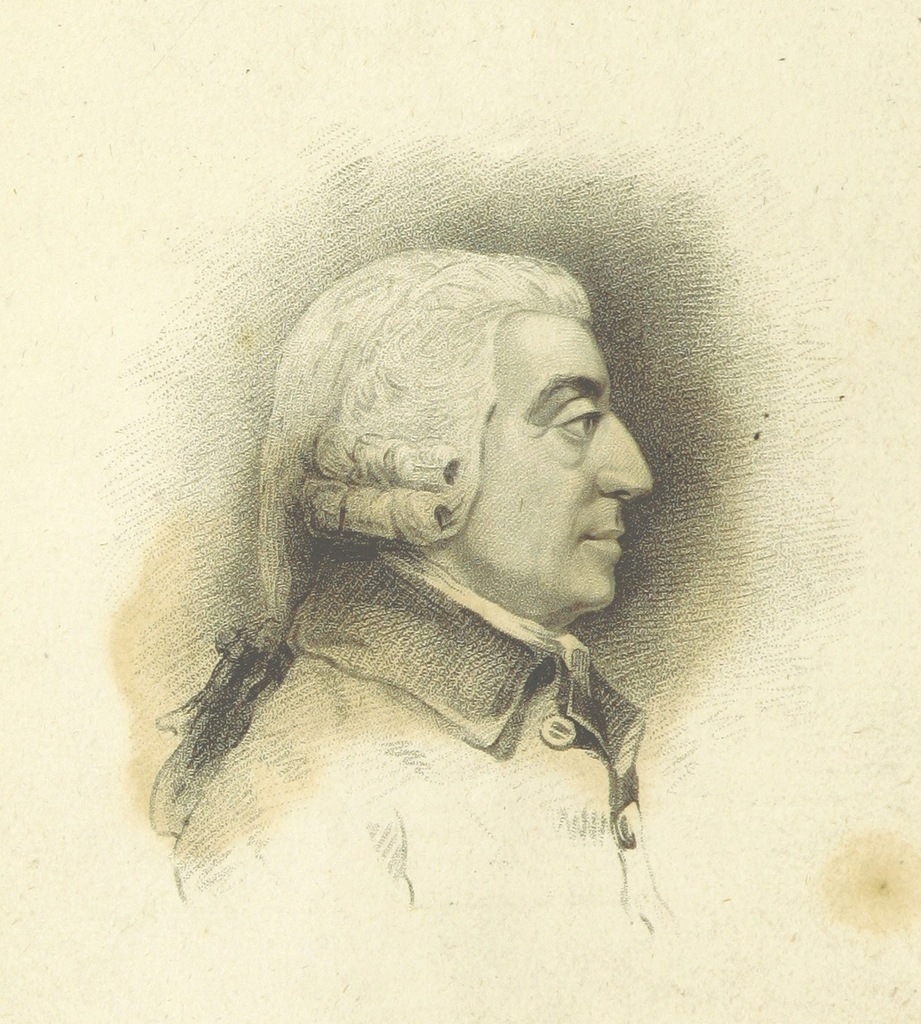

Adam Smith has left the world with an enduring legacy. Written in the 18th century during the early years of the Industrial Revolution (1760-1840), his treatise on An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of the Nations55 has transcended generations. Despite the radical and powerful forces that have continued to transform our world environment, the Wealth of Nations remains relevant today. One of the world’s greatest pioneers on the political economy, Adam Smith in the Wealth of Nations outlined the intellectual framework for the functioning of the free market economy.

The legacy of Smith

The main premise in this monumental work is that the division of labour, together with rational individual self-interest, would produce an equilibrium that would be beneficial to the overall community. In essence, the price system would accurately capture the accumulated preferences of investors and consumers in the functioning of the free market economy.

Famously describing the unseen forces driving the market as “the invisible hand”, Smith maintained that the equilibrium generated would result in economic prosperity that would be beneficial to society. He asserted that any interference with such free competition would likely be injurious to the economy, absent a compelling reason to intervene.

While his ideas and principles articulated have provoked much debate, it continues to be relied upon as an intellectual framework from which powerful solutions can be derived – while being contextualised in dramatically different environments. Years later, Milton Friedman described this phenomenon as “cooperation without coercion”.[1]

Unlike some of his contemporary followers, however, Adam Smith did recognise that certain parts of the economy did require targeted intervention by the state. Book V of the Wealth of the Nations represents his overture into the role of the state within his core thesis of the laissez faire market economy.

In it, Smith acknowledges that the invisible hand did indeed need a helping hand from the state to achieve a good life for society. However, Smith clearly stated that this should be targeted and limited in scale with the responsibilities of the government being confined to specific areas as outlined in Book V. He emphasised that production and should still be predominantly privately owned.

The global economy

In the generations since, we have experienced fundamental changes to our environment in terms of the productive capacity and interconnectedness of the global economy, both shifts anticipated by Smith’s focus on the transformative power of the division of labour. As we fast forward into the contemporary world, these changes have been even more profound and transformative.

Alongside these positive changes to the global economy, the world has also becoming increasingly disordered with extreme and unstable conditions. These have arisen from a range of major global disruptions – including the catastrophic consequences of the global health pandemic, the climate change crisis and the accelerated advances in technology which have cumulatively led to unimaginable changes in how business is conducted and how we live our lives.

Some of these developments are also reinforcing other systemic issues, such as indebtedness and inequality. The world has also become more vulnerable and prone to recurring crises with highly damaging consequences on the environment and on humanity. How relevant then are Adam Smith’s ideas to this contemporary environment? Equally importantly, how relevant are these ideas to a developing world that is becoming increasingly significant in the global economy?

The duties of the state

The most urgent and pressing issue confronting contemporary economies is sustainability. This essay will examine the ideas proposed in the fifth and final book of the Wealth of Nations and whether indeed it provides an intellectual framework for solutions to this challenge. What would Adam Smith have said on such issues surfaced by the climate crisis and the interventions being envisaged to address them?

For several of these complex and ambitious agenda, neither the market nor the state can achieve the aspired outcomes on their own. Is there then an optimal arrangement in which the private sector can participate collaboratively with the government in the provision of the public goods that would not cause injurious outcomes alluded to in the Wealth of Nations?

Also considered is its relevance to emerging and developing economies. This essay will also discuss some of the pre-conditions that would be needed for the effective functioning of the free market and for generating the optimal outcomes envisaged in the Wealth of Nations that would benefit society.

As mentioned previously, Book V of The Wealth of the Nations highlights that, while private markets function more efficiently and are more productive to create the best outcomes for a nation, there are specific areas in which intervention by the state is required. Covered in three Chapters, Book V discusses the specific areas that should be the responsibility of the sovereign, how these responsibilities might be managed and financed including his views on public indebtedness.

He believed that the most important responsibility of the government is to protect society. He asserted that the first duty of the state was to provide protection from the dangers to society, which during that time was predominantly against violence and crime and from invasions from other nations. The state therefore needed to provide a policing and military force, to be maintained for this purpose and eventualities.

The second duty of the sovereign, as identified in Book V, is to protect members of society from oppression and injustice. Smith believed that such actions and crimes were driven by avarice. A justice system was therefore an integral part of the system to provide protection to society from such crimes. The third duty of the state concerns its role in providing the supporting infrastructure and public works that were considered as vital for the well being of the society.

This part of his work foreshadows the modern thinking on public goods. While the state had an important role, Adam Smith was still of the view that it should be as limited as possible and that such activities would function more efficiently if it was privately funded. In Chapter 2 of Book V, Adam Smith outlines the sources of revenue to provide funding for the public expenses outlined in Chapter 1.

Here, the most enduring contribution is his conception of the tax system which he believed should be proportionate to the ability to pay and have sufficient clarity to avoid any ambiguity while also being convenient. Such taxes should also not be any more than that required for the functioning of the state. Additionally, if the taxes were not well formulated it would not only affect pricing but could result in distortions.

He also discusses at length the corporate structure for such public works, believing private institutions would be superior to public ones. He was not keen for public companies, noting that the separation of ownership and management could not only lead to negligence, but it risked managers to profit at the owner’s expense [2]. He nevertheless suggested that for activities that required a lot of capital, such as those for financial institutions and utility companies, that it would be best managed by a group of persons.

In Chapter 3 he raised warnings on overborrowing by the government and maintained that if spending is unchecked it would result in the ruin of nations. Specifically mentioned in Book V is the provision of education by the state, essentially considering it as a public good. Adam Smith also believed that everyone should have access to education. He was an early advocate for inclusion and being inclusive on grounds that it would increase the potential of the labour force.

While tuition fees should be charged to the students, he also had the view that it should be made available to the poor and that such education should be subsidised and paid for by the state. He maintained that a more educated society would be better positioned to make better choices, thereby making for a more orderly and prosperous society. Indeed, for emerging and developing economies, this is the one single manner in which poverty can be eradicated and for inequalities to be reduced.

From public goods to climate action

Knowing Smith’s position on public goods, what can we surmise that he would have said about the planet? Under the public goods framework, the planet can essentially be considered as the ultimate public good, with the stock of natural resources that includes the air, soil and water that has been bestowed upon us by nature. With decades of negligence and plundering of nature, the owners of capital in this era have an additional responsibility and accountability – to ensure the sustainability of our planet.

Until now, the planet has contributed towards sustaining human life. For those of Smith’s era, the idea that human activity could permanently damage the capacity of the planet to sustain humanity would have seemed unthinkable. However, as we well know, it is now at risk of being destroyed and depriving our future generations of the means to provide for themselves [3].

The protection of the environment would certainly fit with Adam Smith’s overall framework described in Book V. It would not be inconsistent with his premise that state interventions are necessary in the areas in which the agenda to protect the well-being and, indeed, the very security and existence of humanity. In this particular instance, the need to avert a climate catastrophe provides not just clear grounds for state intervention, but that this is in fact one of the most important responsibilities of the state.

The contemporary reality of environmental degradation has now prompted urgent attention. Three fundamental reasons explain this urgency. The first is that staying on this trajectory without action will render our planet no longer habitable in the long term, due to atmospheric conditions with high concentrations of carbon dioxide, amongst other pollutants, along with the resulting extreme temperatures and increasingly frequent natural disasters.

The second fundamental reason for urgent action is the immediate repercussions on human livelihoods arising from droughts and floods, and the third is the overall irreversible physical damage to our entire eco-system. Cumulatively, these outcomes are affecting health, food security and lowering the potential for economic growth and employment. These developments have therefore called for action to be taken for the protection of society from these risks and eventualities.

However, given the enormity and scale of the climate crisis being anticipated, it cannot be addressed by the state alone. Necessarily, it requires joint actions and combined efforts from the public and private sectors to avert the biggest challenge faced by humanity. Again, this is not inconsistent with the point made in Book V by Smith, that one of the fundamental responsibilities of the state is to protect its citizens and their livelihoods.

Interventions to support the climate change agenda have recently been centered on the objective of transitioning economies to net zero emissions. In addition to investments made by the state to respond to the risk of a climate related crisis, the interventions have ranged from providing the incentive structure to achieve these goals to the implementation of specific and targeted environmental regulation.

In the case of the former, the discussion on appropriate design of taxation in Book V can for example serve as a guide in the imposition of charges for emitting greenhouse gases to thereby determine an appropriate pricing for such activities, an example of the enduring power of Smith’s work. In the case of the latter, it has included compliance to standards, such as on transparency and disclosure, in addition to prudential regulation and guidelines.

Within financial systems, financial institutions have taken on an increasingly important role in the financing of investments in this domain and in the channeling of funds to the various respective sectors that support sustainable technologies, while avoiding those investments related to high carbon activities. The increased requirements for disclosure of information in effect strengthens the invisible hand [4].

It provides information on the risk taking that may damage the environment by the investment. It is maintained that such market discipline provides a powerful mechanism to constrain excessive risk taking [5]. Other policy measures and tools applied to preserve financial stability include the adoption of stress testing applied to financial institutions. Such tests now incorporate assumptions on the risks of climate-related shocks.

It also includes guidelines for incorporating environmental issues into their risk management processes. In several emerging economies in Asia and in Latin America, it has also included measures such as guidelines for loan documentation that require compliance with environmental standards and efforts taken to advance green financing in the capital markets.

To promote this asset class in South East Asia, the ASEAN Green Bond Standards were introduced in November 2017 [6]. Further interventions have also included direct spending by the public sector on green physical infrastructure. Initiatives have also been taken to develop a common language to facilitate understanding and progress in taking the agenda forward.

Notably, the ASEAN economies have also commenced work on the Taxonomy for sustainable finance, similar to that in the European Union, to be completed in 2021.[7] Given the magnitude of the ambitions to address the climate change agenda, the goal to transition to low carbon economies cannot be achieved by governments alone. There needs to be increased investment activity by the private sector that embeds environmental considerations.

Such investments by the private sector have included those that aim at providing technological solutions to environmental problems, such as wind, solar power and hydro plants and other potential renewable energy generations.[8] There are also investments in other sectoral industries such as climate-aligned investments in agriculture. Finally, there are also the investments both by the private and public sectors in energy efficient public transportation, water, electric vehicles and green buildings.

What are the elements that would draw the market process to support such activities? Several initiatives have already been implemented to encourage and facilitate such investments. Broadly, it has included initiatives to align the market to the medium- and long-term targets to be achieved, such as the SDGs, improving the overall investment climate and the removal of counterproductive policies such as barriers and impediments for such investments.

Central to this is having in place the incentives that generate the appropriate carbon pricing. A further key initiative is the integration of the climate change agenda into the governance arrangements of businesses. Most of all, boards now have a duty to address climate issues. It is an opportunity for shareholders to influence corporate behavior in addressing this climate change agenda.

The command of knowledge and expertise on the subject matter is equally important. Finally, most companies now release a sustainability report on their strategies, progress and achievements in contributing towards the transition to a low carbon economy and towards environmental sustainability. Overall, this is indeed only a start. Encouraging is the momentum of further policy actions that harness both the strengths of the public and private sectors to advance this agenda.

Amidst the urgent concerns on the prospective climate change crisis, emerging and developing economies while being part of this agenda, are also transitioning towards becoming more market-driven to achieve greater development and progress. Experience has indeed shown that economies that have moved to accelerate deregulation to achieve greater market orientation and heightened liberalisation to participate in more competitive international markets have benefitted immensely in terms of the contribution to their growth and prosperity.

However, during periods of significant shocks, such economies have tended to experience greater damaging consequences [9]. The lessons that have been drawn from these experiences are that important pre-conditions need to be in place prior to deregulation and liberalisation and the move towards a more market driven economy.

Among them are to have strengthened financial institutions, developed financial markets and the necessary information and payment systems that are in turn reinforced with a developed and robust regulatory and supervisory oversight and that is supported by sound governance and risk management practices. These financial reforms which were implemented in many emerging economies in many parts of the world have indeed increased their resilience during the 2008-2009 Great Financial Crisis in the developed economies.

While the emerging economies were affected by the crisis, it did not trigger a financial crisis in their economies. Such risks, however, are always present. The 2008-2009 crisis also demonstrated that even developed financial markets have not been immune to becoming dysfunctional when confronted with extreme shocks. A further lesson is that policy tools such as ‘market maker of the last resort’, recently been implemented during extreme conditions to avert the severe consequences of a financial crisis.

Such interventions have generally been accompanied by conditionalities to address moral hazard concerns. Necessarily they have also been targeted and temporary. Finally, to conclude on the subject of Adam Smith’s premise that the invisible hand essentially translates the pursuit of self-interest into a public benefit. He believed that self-interest will eventually enrich the whole community.

It was in his earlier work, ‘The Theory of Moral Sentiment’, that he provided the ethical, philosophical and psychological underpinnings to the Wealth of Nations. He maintained that social psychology gave a better explanation to moral action than reason. He believed that overall, man would act in the best interest of others. “How selfish so ever man may be supposed, there may be some principles in his nature, which interests him in the future of others and renders their happiness necessary to him, through it derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it”.[10]

From this, it can be interpreted that, had Adam Smith lived in the twenty first century, he would have been a strong voice and advocate for the protection of the environment, including to the risks that may have intergenerational implications leading to higher overall costs to our planet and humanity. In this case, the call would be for urgent action from both the state and the market to deliver an outcome that would allow our progress and prosperity to be enjoyed by our future generations.

Citations:

[1] As quoted in many of his works, including Friedman, Milton and R.D. Friedman (1962), Capitalism and Freedom.

[2] Indeed, this illustrates Adam Smith’s intuitive understanding of the problem of moral hazard before it was formalised in the modem literature

[3] Forcefuliy presented in Dasgupta, Partha (2021), The Economics of Biodiversity

[4] At the institutional level, banks and financial institutions now publish the criteria that is used to assess, monitor and report the green impact on the investments that is being undertaken. Global Alliance for Banking on Values (GABV) is a network of leaders from around the world that commit to advancing positive change in the banking sector to environmental sustainability. This is through transparency in terms of their assets that are committed to meeting the needs of the planet.

[5] A parallel can be drawn in the world of financial regulations in relation to financial stability in which financial regulation reinforce market discipline to internalise systemic risks. Bernanke, Ben /2007), Financial Regulation and the Invisible Hand

[6] ASEAN economies, comprising of ten countries in South East Asia, with a population of 600 million, and collectively in terms of the size of their economies. it is now the fifth largest country in the world.

[7] AFMGM (2021), Joint Statement of the 7th /\SEAN Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors’ Meeting

[8] The 2016 IFC Climate investment Opportunities in Emerging Markets, An IFC Analysis provides an account of the progress in such investment in these respective regions.

[9] Discussed at length in Zeti Aziz (2014), Managing Financial Crisis in an interconnected World: Anticipating the Mega – Tidal Waves. Per Jacobsson Lecture http://www.perjacobsson.org/

[10] This quote is from the first line in Smith, Adam (1759), The Theory of Moral Sentiments.

About the Author

![Conversations on Central Banking: Building Resilience and Policy Frameworks [Webinar Recap]](https://asb.edu.my/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/20210928-WebinarRecap-ThoughtLeadership.jpg)

![Conversations on Central Banking: Bloated Central Bank Balance Sheets [Webinar Recap]](https://asb.edu.my/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/20210927-WebinarRecap-ThoughtLeadership.jpg)