Nothing evokes more emotion and debate in the asset management industry than sustainable investing. Pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, central banks and other asset owners are mandating that asset managers adhere to environmental, social and governance principles. But some politicians think that sustainable investing is just a lot of hype.

According to the Global Sustainable Investment Review, total assets under management for responsible and sustainable investing reached US$35.3 trillion in 2020. And Morningstar reports that assets managed by global sustainable ESG mutual funds reached approximately $2.8 trillion by the second quarter of 2023 in spite of high inflation and interest rates and fears of a recession.

In the academic world where separating fact from fiction is a professional calling, scientific evidence is paramount. Past studies have not been able to find conclusive evidence of positive correlation between ESG characteristics and equity returns. In fact, recent theoretical literature argues that “green” assets should earn an expected return that is lower than “brown” assets due to investors willing to forego good returns for ESG’s social good.1

Yet, common sense and financial intuition dictate that a simple financial economic model of an investor with a more generalised profit maximising objective, where negative externalities and social costs are explicitly minimised, would yield the opposite result. This would also be the case where hedging demand arising naturally from an investor’s desire to hedge against, say systematic climate risk, creates demand for securities that are correlated with climate risk.

Indeed, Nobel laureate Robert C. Merton’s seminal paper more than 20 years ago linking consumption preference with portfolio selection and investment rules in a dynamic context, proved theoretically that there is in fact linkage between these concepts.2

Flexibility can add significant value to irreversible investment opportunities, which encompasses ESG investing principles.3 Referred to as “real options analysis”, this approach accounts for the value of flexibility, or optionality, in the investment opportunity set.

Flexibility capitalises on upside opportunities while reducing exposure to downside risks, thus adding risk-adjusted value in the process. The net effect of all this, in the context of ESG investing, is that it increases demand for green assets over brown, thus improving the expected return of the former over the latter in the long run.

The literature

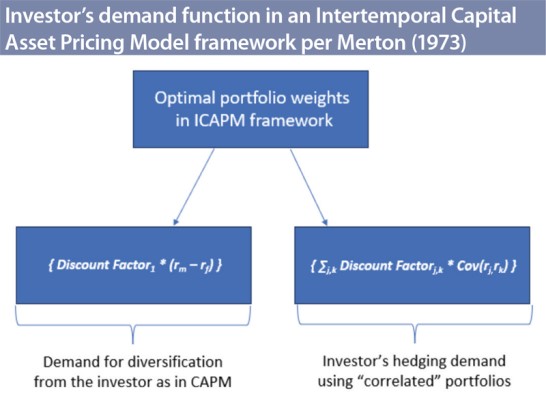

In his 1993 paper, Merton demonstrated that the equation of motion for an investor’s demand function for assets within the multifactor Intertemporal Capital Asset Pricing Model (ICAPM) framework satisfies both the diversification (i.e., the single-period CAPM model) and hedging (i.e., the risk management) demand components. That is, the investor’s desire to hedge against various financial market-based systematic risks gives rise to demand for portfolios that are correlated with those market-wide risks.

The multi-dimensional demand function of the investor in Merton’s ICAPM framework yields both demand for the well-understood, mean-variance optimisation diversification motive found in MBA textbooks, along with demand for hedging portfolios.

In other words, if there indeed exists a financial economic situation where ESG regulations, rules, perceptions, risks and boundaries are binding, they would naturally give rise to hedging demand from investors for green assets, which would result in an “equity greenium effect”.

A simple and easy to follow pictorial will illustrate the point. Merton’s analysis demonstrated that the investor’s demand function in the ICPAM context represented by a set of portfolio weights, w*, is given by:

The demand function on the left-hand side of the figure states that the amount invested in a particular portfolio, w*, is the product of a discount parameter and the risk premium earned on portfolios that are correlated with the market-wide systematic risk factors in the economy. In the ICAPM case, there are two components, which are given by the left-hand side and right-hand side of the figure

The first expression,

{Discount Factor1 * (rm – rf)},

is simply the demand for diversification from the investor, vis-à-vis the desire to hold a diversified market portfolio of (risky) securities, which is given by the textbook mean-variance optimisation scheme a la CAPM.

The second expression,

{ ∑j,k Discount Factorj,k * Cov(rj,rk) }

asserts that the investor’s demand for hedging portfolios helps to insure against other systematic risks in the economy, including unanticipated inflation, future changes in the yield curve, and even changes in ESG requirements and ESG systematic risks with the passage of time.

In other words, a risk-averse investor would naturally like to avoid or hedge any reduction in the individual’s usual consumption programme due to the unintended consequence of a particular systematic risk variable’s (future) effect on the individual’s (future) wealth level.

For instance, let’s assume that polluting the environment, which we shall call the bad climate factor, hurts both our pockets and our lungs. The economy and our wallets will invariably take a hit. In that scenario, green assets, where returns should be positively correlated with the bad climate factor, will presumably earn an extra ex post (or realised) risk-adjusted return over brown assets, compensating the investor for the hit to the wallet, while brown asset prices will face a decline. The green assets hence serve as the hedging portfolio.

As a consequence, if demand for non-ESG assets drops due to them being brown, the ex-ante expected return of such assets is expected to go up in a commensurate manner. The opposite happens in the case of green assets. This is also exactly as Merton predicted in his paper.

In fund management speak, green assets are like traditional multi-asset managers with steady earnings from management fees in all states of nature, that is, fees from cash and money market funds in unfavourable states of the economy, and equity growth funds in the good. Meanwhile, proprietary trading desks that are highly leveraged to the economy with highly variable earnings, should have a much higher cost of capital, and hence, higher expected return, than the former.

In summary, investors will earn an expected return commensurate with two sources of return premia: systematic risk-bearing activity that is market-driven (i.e., CAPM or mean-variance diversification), as well as from risk-bearing activity from unfavourable movements in the economic state space (i.e., hedging activity). The premium earned from green assets is referred to as “greenium” in the academic literature.

Empirical evidence

Indeed, very recent empirical evidence appears to indicate so. In the case of US stocks, Lubos Pástor, Robert F. Stambaugh, and Lucian A. Taylor (2022) found that green stocks outperform brown stocks by a cumulative 174% over the sample period from November 2012 to December 2022.4

Another recent working paper from Cornell University also showed that green stocks around the world, including Asia, do earn higher returns than their brown counterparts over a sample period covering December 2012 to December 2021. However, there is inherent variation in the green risk premium across time and geographies.5 For example, the authors observe a marked reduction in the greenium effect since January 2016.

We surmise this could be due to the Paris Agreement coming into force in 2015 after 196 world leaders emphatically acknowledged the importance of combating climate change via a legally binding treaty. This was followed by the largest public pension fund in the US mandating sustainable and responsible investing in its investment strategies the following year.

These two significant events could have had a marked and immediate effect on demand for ESG-compliant assets, hence increasing prices and reducing expected returns.

Deploying the strategy

There are two ways in which asset managers can benefit from these academic results. They would first need to create a long/short return strategy by ranking the stocks in their stock universe according to an appropriate and effective ESG rank, or “greenness”. Then long the top quintile and short the bottom quintile to create a long/short return spread portfolio, which can either be equal-weighted or cap-weighted.

The managers could then use the “greenness” return spread portfolio in two ways: as a risk factor, just the way the stock returns generating process is linked to the four Fama-French firm systematic risk factors, popularly known as market, size, value, and momentum; or as an alpha factor, the way hedge funds form long/short portfolios from alpha generators.

If they use it in the second way, any long/short alpha premium can be enhanced by installing a judicious amount of leverage. For example, a 2022 study by Pastor et al. indicated that the value-weighted long/short portfolio of US stocks in the top third of greenness outperformed the bottom third by a cumulative return difference of 7.8% per annum.

Despite the scepticism of ESG naysayers, there appears to be value to betting on the green premium. This is good news for managers who create portfolios by following the true greenness of stocks in their universe through a sound ESG ranking scheme.

While the greenium seems to be decaying over time due to the price pressure effect as trillions of dollars flood the sustainable and responsible investing universe, it just means that ESG stocks are becoming more fairly priced with the passage of time.

* Joseph Cherian is deputy chief executive officer and practice professor of finance at the Asia School of Business in Kuala Lumpur and visiting professor at the Cornell SC Johnson College of Business in New York. He thanks Andrew Karolyi, the Harold Bierman Jr. Distinguished Professor, and the Charles Field Knight Dean at the Cornell SC Johnson College of Business in New York, for his extremely helpful comments and guidance in the writing of this commentary.

For additional working papers in this area, readers can look to the following:

- Do ESG Factors Influence Firm Valuation? Evidence from the Field. Franck Bancel, Dejan Glavas, and G. Andrew Karolyi, Cornell University Working Paper (February 2023).

- The US equity valuation premium, globalization, and climate change risks. Craig Doidge, G. Andrew Karolyi, and René M. Stulz, Fisher College of Business Working Paper (March 2023).

- In Search of the True Greenium. Marc Eskildsen, Markus Ibert, Theis Ingerslev Jensen, and Lasse Heje Pedersen, Copenhagen Business School Working Paper (March 2024).

1 Sustainable investing in equilibrium. Journal of Financial Economics, 2021, 142, 550-571, Lubos Pástor, Robert F. Stambaugh, and Lucian A. Taylor. The authors do demonstrate the special case when green assets have higher realized returns then brown assets. This happens when investors’ demand function abruptly and ubiquitously turn green!

2 An intertemporal capital asset pricing model, Econometrica, 1973, 41(5), 867–87, Robert C. Merton.

3 Flexibility is key: Financing net zero, Asia Asset Management, print & online Editions, November 2022, Vol. 27, No. 11, Michel-Alexandre Cardin and Joseph Cherian.

4 Dissecting green returns. Journal of Financial Economics, 2022, 146, 403–424, Lubos Pástor, Robert F. Stambaugh, and Lucian A. Taylor

5 Understanding the Global Equity Greenium, G. Andrew Karolyi, Ying Wu, and William W. Xiong, Cornell University working paper (April 2023).

Originally published by Asia Asset Management.