This blog is a thought piece and synthesis informed by the ASB webinar “Marketing for a New Normal” held 29 April from 3:00pm to 3:45pm. This features insights from Willem Smit, Assistant Professor of Marketing at ASB, as well as from guest speakers: Arun Menon, Managing Director of IPSOS Malaysia and Jocelyn Pinto, Manager, Data Strategy and Analytics at ADA.

No firm can accurately predict what the “new normal” will be, but there are ways to get ahead of the curve in finding out what that a new post-COVID reality looks like. In a race against the clock, it is very tempting to act quickly, but before jumping into action, marketing professionals and brand managers need to ask for themselves the following elementary questions first:

- Consumers staying at home: what is going on? What does the data tell us?

- Post-COVID when they come out of their homes: will there be a “new normal”?

- How should companies respond to a rapidly changing customer reality?

To give up-to-date market insights into these elementary questions, we have leaders in customer intelligence, global market research company IPSOS and the regional’s largest data-driven agency ADA, share their current consumer observations. Based on their observations and evidence-based recommendations from Marketing Science, we as a panel distilled the following eight lessons for preparing for different future scenarios of a New Normal.

Question: What is the best marketing strategy for a firm facing a recession?

Recessions and downturns are not new and have been a topic of study for a long time. To systematically learn from what we have learned from those past experiences, we turn to Marketing Science, and specifically to empirical studies examining the survival and success of firms and brands going through recessions, downturns and crises. We find two clear Don’ts for marketing strategy in a downturn.

Lesson 1: Don’t cut marketing spending.

While everyone including your rivals are affected by a recession, it is important to stay competitive. Cutting your marketing budget during a recession is not a good idea as it harms your long-term performance. Studies have shown that it is critical to keep “share-of-voice” in the marketplace as firms which reduced spending experienced a signifiant loss in market share coming out of the recession.

Lesson 2: Don’t use price promotions.

It makes sense to become lean and cut the regular price in a recessionary market, as many more consumers have become more price sensitive. However, if you don’t have enough resources to sustain a lower price level and you can only afford a temporary reduction in price, don’t do price promotions.

Once you have to return prices to the higher original level, you will disappoint and lose customers in the long run. Furthermore, the effectiveness of price promotions very much depends on consumer sentiments. When people are generally not in a good mood, promotions lose much of their effectiveness as advocates of a certain product or brand.

Question: Is this [recession] going to be a “normal” recession?

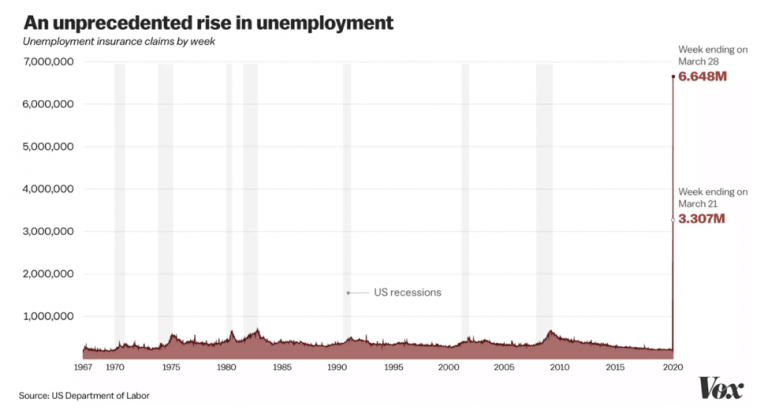

If this downturn was comparable to previous ones, it would be easy to base our expectations on the experiences from our recent past. The 11 post-World War recessions in the US lasted 8-11 months on average. But is this going to last 8 or 12 months?

Lesson 3: Understand this true uncertain nature of the COVID-19 downturn.

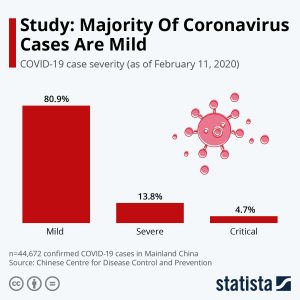

Given the unique nature of the COVID-induced nature of the recession, it was initially expected that it would be a V-shaped recession: a quick dip followed by a rapid economic rebound. However, flattening the curve is taking longer than expected in most countries; While China seemingly managed to do it in 7 weeks, other countries may take longer.

In this unique downturn, the exogenous factors are unprecedented. In the sense, the turbulence and risk is one of true uncertainties, as described by the famous economist Frank Knight: an uncertainty of an “unknowable distribution.”

Lesson 4: Increased variability requires a higher need for continuous market intelligence.

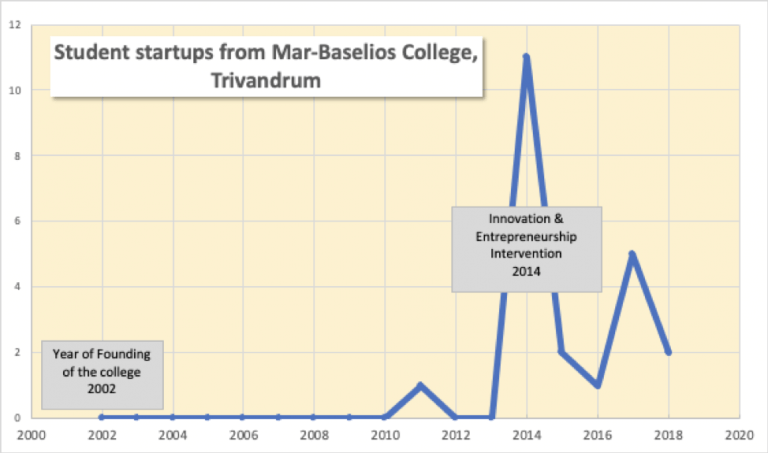

Now that globally a V-shaped rebound has become unlikely, and the COVID-19 uncertainty has introduced a “period of forced experimentation” during which consumers, firms, schools, governments and other stakeholders had to adopt digital technologies, rethink work practices (WFH), design 6 ft procedures, managing clogged-up global supply chains, etc.

So many changes in such a compressed amount of time. Therefore, it is important to know where these new directions are leading to, over time. Yet, it is not possible to gather information about the market by means of our traditional information channels. We are faced with empty streets, consumers at home and businesses split in essentials and non-essentials. There are fewer places to make in-person observations to sense what is going on. However, market research companies and big data firms can fill the gap for these insights and help make this “new reality” less opaque and more transparent by making the distributions more knowable.

Question: What is going on with consumers staying at home. What are they doing and thinking about in this lockdown situation?

Lesson 5: Discover new consumer moments for brand connection without being opportunistic.

While the world is self-isolating, society and people do not live in isolation. IPSOS research shows that home-bound consumers are finding ways to stay connected and communicate. Observable changes are the rise in popularity of topics like managing mental health, celebrating life events virtually, and finding new activities to do in quarantine among others.

These new conversations have led brands to revaluate and reactivate their purpose, relevance, and ways of engaging with their consumers. In order to place themselves strategically and meaningfully in the midst of the chatter, brands must remain authentic and faithful to their identity. Brands need to find the right tone and story to tell within the context of COVID-19 which has revolved around being caring and compassionate. It is also important to remember not to pander too much to your consumers and retain a level of authenticity when engaging. Finally, understand the personally groups in your market and create a strategy for how to reach out to them meaningfully.

Lesson 6: Understand the different consumer responses to COVID-19.

A study conducted by ADA of over 400,000 applications yielded insights into eleven types of “COVID-personas”. Each persona represents a type of mindset as shown through their app-behaviors consumers use the most.

While some personas are more financially minded, others are health-conscious and searching for apps to support their physical and mental health. Another type is more forward thinking, traveling in their mind to places abroad and hoping to go on a trip soon again. What these personas really highlight is the fact that people are in different mental space in current times and this underscores the importance of brands in reaching their customers with the relevant messaging.

Question: When consumers come out of their homes, will they see a new normal?

Two extreme perspectives on the New Normal prevail. The first view is that a new normal will emerge as a result of an intense period of “forced experimentation.” More working remotely, more online shopping, both digital and distance have become new norms post-COVID.

The opposite point of view is that people are hard-wired and will go back to normal and return the old ways of doing things before COVID-19. This view strongly believes that life experiences and activities such as in-person classes, grocery shopping will come back at the same level and virtual options will stay limited.

Question: How should companies respond to a rapidly changing reality?

Lesson 7: Personalize your marketing to the new COVID-19 personas.

Absolutely crucial for marketing professionals and their firms is to understand and cater to each unique persona differently and strategically. To spread a same message too broadly to hit all personas at the same time makes the brand tone-of-voice sound too generic and unable to resonate with people’s varying mindsets especially in the context of COVID-19. Worth noting across all personas is that they all react in different ways which makes it doubly important to remain relevant to consumers.

Lesson 8: Anticipate the phases your consumers are going through.

The path towards regaining momentum post-COVID will be gradual and go through different phases. IPSOS research in China on post-lockdown communities showed that some residual feelings of uncertainty and fear may still affect consumer behavior. Taking advantage of these changes in consumer behavior can be done by anticipating and creating engagement phases.

This starts with the “preparation phase” where the consumers are re-familiarizing themselves with your brand, followed by the “adaptation phase” in which consumers adjust to the limitations of their context and what they can buy. Now consumers are moving into the “anticipation” phase where they are looking forward to releasing lockdown measures. Once a sense of predictability has been established, consumers and marketers enter into experimentation where the desire to explore new things fuels creativity and innovation.

This applies to how consumers create new food options, for instance, out of what they have and brand creating new aspects to their products to spur greater creativity. The last phase is expectation. Both consumers and marketers must accept that the road ahead will still be rife with changes which requires greater agility and creativity to be able to respond to the next six months.

Conclusion

There is no playbook for marketers on how to deal with a global recession caused by a global pandemic. Critical is to avoid taking unproductive and ad-hoc responses to a downturn. Don’t cut the marketing budget and don’t start giving price promotions, because the length of this recession can be unpredictably long. The first step is to intensify market intelligence capabilities to learn quickly from keeping the fingers on the pulse of new evolving developments.

The lessons and principles are a result of keen observations, analysis and detailed inquiry into how people are navigating the “new normal” and are by no means the golden rule of marketing in a recession. However, it pays to always lean into the observable shifts in people and society to ride the wave of these changes and use these to your advantage as a marketer in the midst of uncertain times.

These changes include the rise of new interests, personas and mindsets shaped by the environment created by the pandemic. This also means marketers must discover new and creative ways of authentically engaging with the different consumer responses to COVID-19 with a keen awareness of their mindsets, behaviors, and even process as we collectively navigate the inevitable new normal.

Willem Smit is Assistant Professor of Marketing at the Asia School of Business and International Faculty Fellow at MIT. His expertise is on marketing strategy; his scholarly work has been around the theme of “Marketing Strategy Heuristics in search of superior performance”, in particularly on the newly revolutionized and digitized decision environments for marketers.

After earning his PhD from the Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University, Willem became a research fellow at IMD, where he also designed and delivered executive development programs for multinational companies in the telecom, pharmaceutical and consumer-packaged goods industries. Before joining ASB, Willem has taught at various schools in the Asia-Pacific region: NUS National University of Singapore, SMU Singapore Management University, TongJi University, Hult Shanghai, and MIT affiliate Malaysia Institute for Supply Chain Innovation.

He can be contacted at willem.smit@asb.edu.my

Send us your enquiry now at contact@asb.edu.my to develop and design a customized program for your organization.